Communicative Theology & Students’ Digital Culture

By Frances Forde Plude

[Presented at the 2009 College Theology Society conference, Notre Dame University.]

When I suggest we reflect upon the impact of today’s global “Information Age”, most people will visualize a tsunami – a huge wave of water (or information) rolling over us, drowning us. Recognize the feeling? I suggest we imagine, instead, an earthquake, where the ground we stand on is rumbling and the buildings around us are shaking, some being demolished and falling around us. The ultimate cause of this disturbance is the seismic shifting of plates underneath the earth’s surface. We see the results of the underground shifts; but the deeper cause of these disturbances lies beneath the surface.

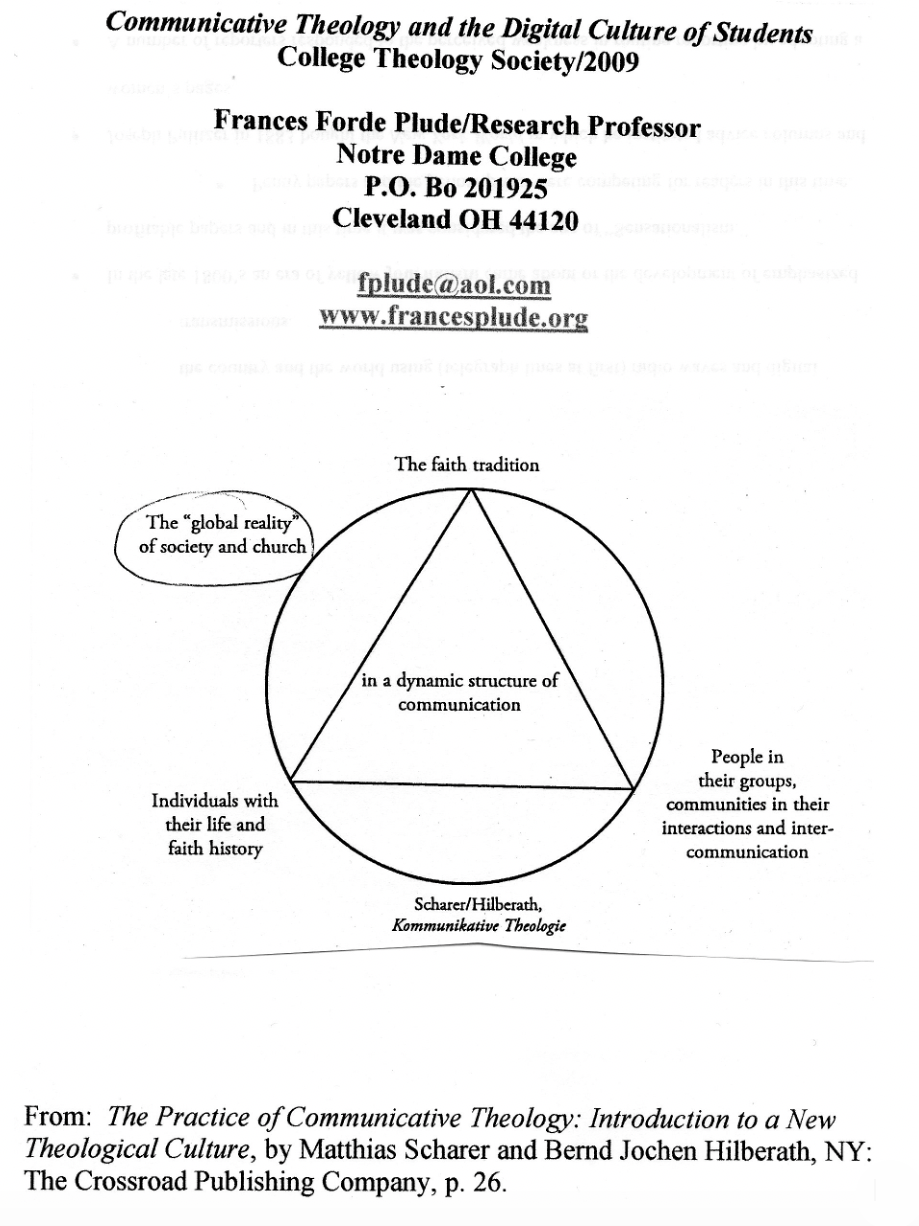

Using this metaphor, I would like to reflect with you upon the model (see Appendix) proposed by Matthias Scharer and Bernd Jochen Hilberath, the authors of The Practice of Communicative Theology: Introduction to a New Theological Culture (Crossroad, 2008). On page 26 of this volume their model, based upon the Theme-Centered Interaction (TCI) model of Ruth C. Cohn, proposes three points of a triangle: It, We, and I, encircled by the Globe. The first point of the triangle is the faith tradition (the “It”); the second triangle point is people in their groups, communities in their interactions and intercommunication (the “We”); and the third point of the triangle consists of individuals with their life and faith history (the “I”). The authors propose that linking these three corners of the triangle results in “a dynamic structure of communication” – because it involves all three: the content, the group, and the individual.

However, the part I want to focus upon in this model is the circle drawn around the triangle: the globe, or what the authors refer to as “the global reality of society and church.” My premise is that the global context of this model must today be understood as a world-wide Information Age – a global network society.

This is the contemporary reality in which individuals (including your students), groups, and faith traditions exist. This reality, this dynamic, of a global network society is the truly seismic shift occurring under the ground we are all standing upon. We see reality around us shifting; we see long-established habits and institutions challenged (in journalism, in churches, for example). But what are the ‘underground’ shifts causing this ‘above-the-ground’ collapse? It is a huge topic. So I’ve organized a format that will help me to communicate lots of information; this will help you to absorb key factors, and it will give you a ‘data base’ you can take home with you to enrich your own thinking and teaching.

I have prepared some fact sheets for distribution (see Appendices). I want to get a lot of data down on paper so we could spend our time thinking about these data, reflecting on their meaning, their impact on us as individuals, as teachers, as members of a faith community. Before sharing these fact sheets with you, let me take a few minutes to share with you my personal journey toward this ‘earthquake’ reality – sort of a “witness” sharing – as I have moved toward our current scene.

About fifteen years ago I was invited to attend a week-long live-in conference in Rome of about a dozen theologians and communication specialists. We were to spend the week in small and large groups discussing ecclesiology and communication. Pat Granfield edited our resulting papers in a Sheed and Ward volume entitled The Church and Communication. My chapter in that book is entitled: “Interactive Communications in the Church.” In this chapter I explore interactive communication technologies as a metaphor for a more dialogical ecclesiology, or theology of church. That was fifteen years ago!

Well, there have been many advances in interactive technologies in those fifteen years. Whether our ecclesiology is more dialogic is not so visible. Incidentally, Brad Hinze has written a marvelous book exploring dialogue in the Catholic Church (or the lack of it), through various case studies. This volume, along with other items, is listed in my reference section below.

Before that Rome conference I left a career as a television producer and on-air host, to do doctoral work at Harvard and MIT – looking especially at the impact of new communication technologies on government policies, on institutions, on religious groups. I remember one of my major concerns entering Harvard was to prepare myself to advocate for less privileged groups as technological tools empowered the wealthy, the already powerful. What about developing nations, with their largely poor populations? What about women, always under-empowered? Who would represent these groups in a more technological world?

So, armed with my Harvard doctorate and this Rome conference experience, I engaged in an academic teaching and research life exploring the integration of communication and theology. This work has resulted in many individuals producing numerous books, conferences and academic papers in a field that came to be known as “Communication Theology.” We conducted annual forums at the Catholic Theological Society of America (CTSA) for a decade. Bob Schreiter and Elizabeth Johnson and others were staunch supporters of this inquiry. The Communication Theology enterprise connects scholars (of various ages, including many younger scholars) all around the world.

Meanwhile, the important Communicative Theology work of Matthias Scharer and Bernd Jochen Hilberath was developing in Europe, representing a wisely pastoral application of theology and communication principles. Another example of this pastoral application is the Virtual Learning Community for Faith Formation – an online program at the University of Dayton.

Along the way, over these fifteen years, another major experience informed my passion for this. I was invited to become a member of a small international ecumenical think tank called the International Study Commission on Media, Religion and Culture. For a decade, our group met each year for a week of dialogue and study in various locales around the world – Africa, Latin America (Brazil and Ecuador), Europe (Rome) and Eastern Europe (Ukraine), Asia (Bangkok and Australia), and North America (Hollywood, Vancouver and Boulder, Colorado). In each location we spent a week communicating with local specialists in religion, media, and culture, and visiting various local sites. These global visits (and the chance to dialogue among ourselves about our own research projects) taught me almost as much as three years of doctoral studies at Harvard University. An underlying reality began to creep into my consciousness: communication studies is not just about communicating; it is also about culture. So now I have had the benefit of experience in TV studios, studies at Harvard, networking with communication theology colleagues around the world, and global conversations about communication, religion, and culture.

And all the while, in my teaching and research in communication technologies, I struggled mightily to keep abreast of the changes: moving from satellites and fax machines, to PCs, the Internet, laptops, wireless connections, cell phones morphing into computers with Internet connections, video streaming on our computers, other personal digital assistants, social Internet communities, video games – all of it. About a year ago I started a serious study of the deeper meaning of the global network society. For today’s presentation I studied two authors and I have shared data from their work in the fact sheets packet I have prepared for you.

The first, Manuel Castells, born in Spain, was for many years a professor at Berkeley, with Silicon Valley right up the road. He authored a trilogy (cited on the fact sheets) entitled The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture. Volume I is the Rise of the Network Society; Volume II explores The Power of Identity (the project of the self and social activism empowered by global networks). And Volume III, entitled End of Millennium, examines the role of the State – the collapse of industrial state-ism in the Soviet Union, the varied financial and governmental policy crises in the Asian Pacific and the unification of Europe. All these volumes explore the wide-ranging and deep ramifications of a globally networked world.

These volumes are encyclopedic! They are filled with statistical data and Castells analyzes global and regional trends many people have missed altogether. He links the ideas of many respected scholars like Anthony Giddens while showing that some concepts, such as the post-industrial society, are flawed. He examines world-wide movements like environmentalism, the global criminal network, and radical fundamentalism. However, Castells also explores the impact of the global network “on the ground” – on issues like global poverty, world-wide and regional employment, and the role of women, for example.

The other author I have shared in my fact sheets is Don Tapscott, who wrote the 2009 volume grown up digital: How the Net Generation is Changing Your World. As you will see in the fact sheet on the Net Geners, Tapscott headed a huge research project to get a factual profile of this population cohort.

With the background I have sketched above, I am more and more engaged in these deep data explorations. I am convinced we are feeling (in our various corners of the universe) the structural damage or collapse of many institutions we have taken for granted. This is a vital part of “The Globe” area of the Communicative Theology model. I will spend a few moments reviewing some of the highlights on the sheets on the global network society and the Net Generation. I will suggest some aspects of these fact sheets that are critical for understanding the other factors listed.

I have also selected two content arenas (world-wide poverty and the fall of patriarchalism, or patriarchy), that are largely impacted by the realities of the global network society. These two areas, I propose, have much meaning for your work as theologians and teachers. Hopefully, you will have some thoughts and reflections sparked by all these data. I will conclude with a few thoughts about the impact of all of this on how we learn today – in classrooms and outside of them. This is a serious challenge for theology professors; I am sure you have felt it already. These fact sheets can serve as the basis for wider discussions among your colleagues and in your classrooms so people can share insights, reactions, or anxieties that are real in your own part of the globe.

You will see the fact sheets are not like a text to be read from beginning to end; they are reference sheets for your further reflection. It is important to note, especially with the Castells data, that this material describes what is; it is not a commentary upon what should be. Based on wide-ranging sources, these data describe the reality of “the information age.”

Reflection on Fact Sheets in Appendices

The Network Society and its Implications

Note especially: Technology Aspects #1; Project of the Self #2, 3

The Net Generation (Net Geners): Note #1, 4, 12, 26

Poverty: Note #6, 9, Africa #10-14; America #15-20

Global Decline of Patriarchalism (Patriarchy): Note #1, 8, 10, 13, 18, 20

Conclusion: Churches Must Face the Challenge of a Global Digital Culture

Over the centuries, churches have invested heavily in many different media – oral storytelling, manuscripts of the scriptures (and church tradition), scriptoria and libraries, print publications, and extraordinary educational efforts bringing literacy to billions. In the twentieth century, many churches early recognized the life-altering impact of film and television; the Catholic Church issued several documents on communication and had Popes who became media icons.

During these centuries, churches focused primarily on using media as channels for “the message” – as an evangelizing tool. Today, seductive entertainment stories, computerized social networks, and a ‘talk-back’ digital reality require a new kind of a church/communication strategy to supplement traditional measures. Computer and communication technologies have merged into huge but highly personalized networks.

These webs of relationships and interactivity are new challenges for church ministries.

Today we understand better that audiences interpret media messages. Meanings are constructed interactively. It is clear an audience’s understanding of a message’s meaning may differ from what the originators intended. Church members must be schooled to be more acutely aware of this.

Multimedia and multi-sensorial communication challenge print- and text-based transmission and the producer-centered construction of meanings.

There are many new ways of communicating today. Media are no longer considered simply instruments of transmission; media are integral to the meaning and construction of culture.

Popular culture is individualized, interactive, and often ideological; this culture captivates huge audiences globally. Today’s religious people must be re-schooled in the cultural aspects of our media work.

In the past churches have often used writing as a means of democratization and peace. In the digital age churches should oppose using media for the total secularization of culture, for violence, and for control by commercial or military forces.

This is a reason to not remain wedded to communication systems of the past. Instead we need to make digital communications an integral part of worship, education, social action, and spiritual formation. The absence of churches from the forces shaping the development of digital communications leaves a huge void in the present global culture of the digital age.

Churches have been concerned with the truthfulness of their message, depending upon the Holy Spirit for the message to take root in human souls. Now, however, religious people face a ‘talk-back’ mediated world. Churches need to respect this dialogue and re-tool their communication-training efforts to prepare individuals, both technically and psychologically, to engage in genuine dialogue using diverse new media.

A new digital communication system and a new way of forming church- and communication- personnel for this digital reality must emerge and mature in the twenty-first century.

References

Babin, Pierre, and Zukowski, Angela Ann, The Gospel in Cyberspace: Nurturing Faith in the Internet Age, Chicago: Loyola Press, 2002.

Campbell, Heidi, “Who’s Got the Power: Religious Authority and the Internet,’ http://JCMC.indiana.edu/vol12/issue3/campbell.html (accessed, May, 2020).

Castells, Manuel, The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture, Vols I-III, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Castells, Manuel, “Communication, Power and Counter-power, International Journal of Communication, Vol 1 (2007), pp 238-266.

Giddens, Anthony, Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age, Cambridge: Polity, 2001.

Hess, Mary E., Engaging Technology in Theological Education: All That We Can’t Leave Behind, NY: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2005.

Hinze, Bradford E., Practices of Dialogue in the Roman Catholic Church: Aims and Obstacles, Lessons and Laments, New York: continuum, 2006.

Horsfield, Peter, Hess, Mary E., and Medrano, Adán M., eds., Belief in Media: Cultural Perspectives on Media and Christianity, Burlington VT: Ashgate, 2004.

Knobel, Michele and Lankshear, Colin, A New Literacies Sampler, NY: Peter Lang, 2007.

McChesney, Robert W., The Political Economy of Media: enduring issues, emerging dilemmas, NY: Monthly Review Press, 2008

Plude, Frances Forde, “Interactive Communications in the Church,” in The Church and Communication, Patrick Granfield, ed., Kansas City: Sheed and Ward.

Plude, Frances Forde, “Communication Theology: An Annotated Bibliography,” in Marriage, Sophia and Mitchell, Jolyon eds. Conversations in media, religion, and culture. Edinburgh: T&T Clark and Continuum, 2003.

Plude, Frances Forde, “Telecommunication Networks: Impacts on Communication Flows and Organizational Structures (Including Religious Institutions), in Cultura y Medios de Communicación, Unuversity of Salamanca, 2001.

Plude, Frances Forde, “A Dialogue on Communication and Theology,” New Theology Review, Vol. 8, No. 4, November 1995.

Plude, Frances Forde, “Technological Changes: A New Challenge for Universities, Students, and Communication Professionals,” Syracuse Scholar, 1990.

Scharer, Matthias, and Hilberath, Bernd Jochen, the practice of Communicative Theology: an introduction to a new theological culture, NY: Crossroad, 2008.

Schreiter, Robert J., “Communication and interpretation across cultures: Problems and prospects,” International Review of Mission, V 85, n 337, April 1996, p. 227

Tapscott, Don, grown up digital: How the Net Generation is Changing Your World, NY: McGraw Hill, 2009.

Teusner, Paul, “Christianity 2.0: A New Christianity for a New Web”, http://paulteusner.org (accessed May, 2009).

Appendices

Fact Sheet/The Net Generation (Net Geners)

[This information, compiled by Frances Forde Plude, is derived mainly from grown up digital: How the Net Generation is Changing Your World, by Don Tapscott, author of the earlier important work Wikinomics].

These data are based on a $4 million research project, funded by large corporations to get a factual profile of Net Geners (who are potential employees and clients/customers). 10,000 people were interviewed globally, 40 reports were produced, and several conferences were held. A global network of 140,000 Net Geners hosted a series of discussions.

These research results indicate that Net Geners are unique in many ways, but the current stereotypes are dangerously distorted.

1. Net Geners range from ages 11 to 31 (in 2008). They outnumber the Baby Boomers and were the first group bathed in the digital culture. They represent 81.1 million individuals, 27% of the U.S population.

2. As employees and managers they work collaboratively (influenced by working in teams as video gamers) and they collapse rigid hierarchies.

3. As consumers they want to customize the products they buy; thus, brands, like Apple, must allow for this product adaptation.

4. In education they want to change the model from a teacher-focused approach to student-based collaborative learning – the 2.0 school. They like peer projects. They value networking relationships, even in learning.

5. As citizens, Net Geners are transforming elections and how citizen-responsive governance is managed – democracy 2.0.

6. U.S. youth have access to 200 plus cable TV networks, 5,500 magazines, 10,500 radio stations, and 40 billion Web pages. 22,000 books are published annually. Global video game sales will be $46.5 billion by 2010.

7. Net Geners want freedom – freedom of choice and expression.

8. Net Geners value transparency: on their own web pages, at work, in government.

9. Net Geners seek entertainment; they value fun at work, in classrooms.

10. This group has a need for speed; they are comfortable multi-taskers.

11. They are innovators and often initiate new products, new ways of thinking. Net Geners are the first global generation.

12. Net Geners view the Internet as connection, conversation, not only information. They produce Net materials (blogs, video, personal sites).

13. By 2007, 72% of 13- to 17-year-olds in the U.S. had mobile phones. This is the medium where most Net Gen action occurs.

14. Net Geners value integrity. Many download music, but they claim, in response, that the industry needs to update its business model.

15. This group is service oriented. The Internet has given them a tool for easily connecting globally for social action and global relationships. 93

16. Over 80% of Net Geners feel more entitled than youth of ten years ago; there is a workplace clash; (half of senior management will retire in the next few years). Youthful innovative creativity will change the workplace.

17. As consumers, Net Geners turn to networks of friends online rather than traditional advertising sources. Consumer advocacy and customer review sites guide product and film choices.

18. Cheap video editing software and simpler interface tools feed the Net Geners’ passion for modifying web pages, products, and work sites.

19. Many Net Geners have ‘umbrella parents’ who exercised oversight, often restricted them from ‘strangers’ so youth found freedom online. They feel close to parents, often live at home longer than previous generations. They prefer a more ‘open’ family, more collaborative, less authoritative.

20. They have been called ‘a political juggernaut.’ They are one-fifth of overall voters; by 2015, when all are old enough to vote they will be one-third of the voting public. They ‘speak’ and vote with networked tools.

21. Based on the Wikipedia model, youth do global digital brainstorming, a world-wide marketplace of ideas and virtual town hall meetings.

22. These youth prefer a more ‘open’ family, more collaborative, less authoritative. This culture will infuse other institutions also.

23. Youth volunteering has increased; network tools empower global activism and Net Gen creativity fuels this passion to ‘connect’ with others.

24. Net Geners are surrendering their privacy (on You Tube, Facebook, etc.); these tools are used in job searches (by employers and Net Geners).

25. In the first week of the release of the video game Grand Theft Auto IV, it sold $500 million worth of games – more than 11 of the top movies in the past 13 years made in the entire year of their release. It is a violent action-adventure game. Yet, the number of serious violent offenses committed by persons 12 to 17 declined 61 percent from 1993 to 2005.

26. As the Net Generation grows in influence, the trend will be toward networks, not hierarchies, toward open collaboration rather than command, toward consensus rather than arbitrary rule, and toward enablement rather than control. This does not mean hierarchies will vanish completely. Society still needs authority and control in various areas.

Fact Sheet/The Network Society And Its Implications

[Compiled by Frances Forde Plude from The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture, 3 vols, by Manuel Castells, 2nd ed.]

“Toward the end of the second millennium of the Christian era, several events of historical significance transformed the social landscape of human life… an (information) technological revolution … globally interdependent economies … social changes like the global decline of patriarchalism… networked social activism… search for identity.”

Technology Aspects

1. The informational, global economy brings a new organizational logic (the network enterprise) with the new technological paradigm: flexible production, industrial cooperation, global and local social alliances.

2. The current technological transformation (2,700 years after the introduction of the alphabet) is of a similar historical dimension—the formation of a hypertext and a meta-language which integrates written, oral, and audiovisual modalities of networked human and data communication.

3. The interactive “technologies of freedom”, cited by Pool, were initiated by governments: French Minitel and the American ARPANET.

4. Computer-mediated communication (CMC) networks presents an openness in the system that allows constant innovation and accessibility.

Economic Realities

1. Informationalism alters the managerial transformation of labor and production. “Myths” of post-industrialism and the service economy have morphed into the informational society, changing employment structures.

2. New technologies allow small businesses to find market niches; this also empowers self-employment and a mixed employment status like flex time.

3. Foreign direct investment drives globalization more than trade. Intra-firm trade represents the equivalent of about 32 percent of world trade.

4. Information technology replaces work that can be encoded in a programmable sequence, but it enhances work requiring analysis, decision-making, and reprogramming capabilities.

5. There is no systematic structural relationship between the diffusion of information technologies and the evolution of employment levels in the whole economy. The specific outcome of the interaction between information technology and employment is largely dependent upon macro-economic factors, economic strategies, and sociopolitical contexts.

The Project of the Self

1. Legitimizing identity is introduced by dominant institutions (churches, etc.) and generates a civil society. Identity for resistance (perhaps the most important) constructs forms of collective resistance. Project identity produces subjects (the desire of being an individual with a personal history).

2. Giddens says self-identity is the self as reflexively understood by the person in terms of her/his biography (“the project of the self”). Nation-state, fundamentalisms, and activism by groups are all identity related.

3. People globally resent the loss of control over their lives, nations, and the environment. Examples: al-Qaeda and anti-globalization movements.

4. National identity is kept in the collective memory of groups.

5. One of the most powerful states in the history of humankind (the Soviet Union) was not able, after 74 years, to create a new national identity.

Social Change and Activism

1. In all societies, humankind has existed in, and acted through, a symbolic environment. A key feature of multimedia is that they capture most cultural expressions, in all their diversity.

2. Networks constitute the new social morphology; the diffusion of networking logic substantially modifies the operation and outcomes in processes of production, experience, power, and culture.

3. Information is the key ingredient of our social organization; flows of messages and images between networks constitute the basic thread of our social structure. Social activism groups are empowered by the Net.

Institutional/Individual Adaptations

1. Time is a scarce resource. There are indications that, in the U.S., leisure time decreased by 37 percent between 1973 and 1994.

2. Today’s communication system radically transforms space and time, the fundamental dimensions of human life. The “space of flows” and “timeless time” are the material foundations of a new age.

Fact Sheet/Global Decline Of ‘Patriarchalism’ (Patriarchy)

[Compiled by Frances Forde Plude from The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture, 3 vols, by Manuel Castells, 2nd ed.]

“Patriarchalism is a founding structure of all contemporary societies … characterized by the institutionally enforced authority of males over females and their children in the family unit…. The patriarchal family, the cornerstone of patriarchalism, is being challenged … by the inseparably related processes of the transformation of women’s work and the transformation of women’s consciousness.” 192

1. In the late twentieth century we have witnessed what amounts to a mass insurrection of women globally against their oppression.

2. The challenge to patriarchalism is one of the most powerful factors presently inducing fundamentalist movements aimed at restoring the patriarchal order.

3. There is a transformation of personality in our society, resulting from the transformation of family structure and of sexual norms. This is interaction between the network society and the power of identity, transforming us.

4. Social and economic factors impact the changing family structure: the dissolution of households by divorce or separation; delay in coupling; partnerships outside marriage; increasing variation in family units; and increasing autonomy of women in their reproductive behavior.

5. The divorce rate more than doubled between 1971 and 1990 in the UK, France, Canada, and Mexico. One Muslim country studied had a higher divorce rate in 1990 than that of Italy, Mexico, or Japan. In the U.S., the divorce rate per 100 marriages rose from 42.3 in 1970 to 54.8 in 1990.

6. By the 1990s, the percentage of single households oscillates between 20 percent and 39.6 percent of all households (24.5 percent for the U.S.).

7. Children born out of wedlock in the U.S. result as much from poverty and lack of education as from women’s self-affirmation.

8. In the U.S., women’s labor participation rate went up from 51.1 percent in 1973 to 70.5 percent in 1994.

9. In most of the world, labor majority is still agricultural (but not for long). Thus, most women still work in agriculture (80 percent of economically active women in sub-Saharan Africa, and 60 percent in southern Asia).

10. There is a direct correspondence between the type of services linked to informationalization of the economy and the expansion of women’s employment in advanced countries. In the U.S. and the UK, 85 percent of the female labor force is in service industries.

11. The supposed submissiveness of women workers is an enduring myth; however, teachers and nurses globally have mobilized in defense of their demands with greater vehemence than male-dominated steel or chemical workers’ union in recent times.

12. Probably the most important factor in inducing the expansion of women’s employment is their flexibility as workers. Women account for the bulk of part-time and temporary employment and for a growing share of self-employment.

13. As women’s financial contribution becomes a decisive factor in household budgets, female bargaining power in the household increases significantly.

14. As women’s identity is redefined, what is negated is woman’s identity as defined by men and enshrined in the patriarchal family

15. There is a fundamental commonality underlying the diversity of global feminism: the effort to redefine womanhood in direct opposition to patriarchalism.

16. A key development from the 1980s onwards is the extraordinary rise of grassroots organizations, most enacted and led by women, in the metropolitan areas of the developing world. This massive, networked action is transforming women’s consciousness and social roles, even in the absence of an articulated feminist ideology.

17. The feminist movement globally display different shapes and orientations, depending upon the cultural, institutional, and political contexts in which it arises. The strength and vitality of the feminist movement lies in its diversity, in its adaptability to cultures and ages.

18. What is at issue is not the disappearance of the family but its profound diversification, and the change in its power system.

19. The feminist global picture varies. In Europe, in every single country, there is a pervasive presence of feminism. There is a widespread feeling in Russian society that women could play a decisive role in rejuvenating leadership. In industrialized Asia, patriarchalism still reigns, barely challenged

20. The ability or inability of feminist and sexual identity social movements to institutionalize their values will depend on their relationship to the state, the last apparatus of patriarchalism throughout history.

Fact Sheet/Poverty

[Compiled by Frances Forde Plude mainly from data in The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture, by Manuel Castells.

1. There are several processes of social differentiation: inequality, polarization, poverty, and misery.

2. Social exclusion creates poverty, barring certain individuals from work.

3. In the past three decades there has been increasing inequality and polarization in the distribution of wealth.

4. In 1998, assets of the 3 richest people in the world were more than the combined GNP of 48 least developed countries, with 600 million people.

5. Since 1980 there has been a dramatic surge in economic growth in 15 countries. But over much of this period, economic decline, or stagnation has affected 100 countries, reducing the incomes of 1.6 billion people, more than a quarter of the world’s population.

6. At the turn of the millennium over one third of humankind was living at subsistence or below subsistence level.

7. In the mid-90s about 840 million people were illiterate; more than 1.2 billion lacked access to safe water; 800 million lacked access to health services; and more than 800 million suffered hunger.

8. Women and children suffer most from poverty: In 1995, 160 million children under five were malnourished, and the maternal mortality rate was about 500 women per 100,000 live births.

9. In Russia, the CIS countries and Eastern Europe, the World Bank in 1999 estimated that 147 million people there lived below the poverty line of four dollars a day. In 1989 the figure was 14 million.

10. In 1950, Africa accounted for over 3 percent of world exports; in 1990, for about 1.1 percent.

11. The continent of Africa suffers from lack of infrastructure, being robbed of its resources, predatory states, huge indebtedness, and aid dependency. (In 1990, Africa was receiving 30% of all global aid).

12. Today there are more than 3.3 billion mobile-phone subscriptions worldwide; there are at least three billion people who do not own cellphones, the bulk of them in Africa and Asia.

13. In Sub-Saharan Africa, urban unemployment doubled between 1975 and 1990, rising from 10 to 20 percent. African food production has declined substantially, making many countries vulnerable to famine, epidemics.

14. By the mid-1990s, Sub-Saharan Africa accounted for about 60 percent of the estimated 17 million HIV-positive people in the world. Poverty limits access to information and to preventive methods.

15. In 1999, 80 percent of American households, or 217 million people, had seen their share of national income decline, from 56 percent in 1977 to under 50 percent.

16. The median percentage contribution of working wives grew from 26 percent of family income in 1979 to 32 percent in 1992; household structure became a major source of income difference between families.

17. College-educated men with 1-5 years of experience saw their hourly wages decline by 10.7 percent in 1979-1995.

18. In 1999 the top fifth of the U.S. population accounted for 50.4% of total income, while the lowest fifth accounted for just 4.2 percent.

19. In the U.S., the percentage of persons with income below the poverty line increased from 11.1 percent in 1973 to 13.3 percent in 1997, that is, over 35 million Americans, two-thirds of whom are white, and rural.

20. In 1993, 38.6 percent of all female-headed families in the U.S. were living in poverty. 19.9 percent of U.S. children were in poverty.

21. Overall, in the global network society, the traditional form of work, based on full-time employment, clear-cut occupational assignments, and a career pattern over the life-cycle is being slowly but surely eroded away (except in Japan.) This new pattern applies mostly to women who fill most part-time or temporary jobs.

22. Dambisa Moyo, a Zambia native, former World Bank consultant, urges investment in Africa instead of aid programs in her book Dead Aid.

23. Nancy Krieger, Harvard professor, notes that the level of income inequality we allow represents our answer to an important question: “What kind of society do we want to live in?”

24. The microloan Grameen Bank started the careers of more than 250,000 “phone ladies” in Bangladesh setting up shop as their village phone operator, with small commissions as people make and receive calls.

25. In some countries poor people are using their cell phones for banking (moving funds to pay for crops, etc.).